Abstract

Background: Effective faculty teaching relies on receiving authentic and actionable feedback from learners. Numerous challenges in collecting feedback result in nonspecific assessments that limit their utility, as evidenced by our institution’s 2021-2022 faculty evaluations. Objective: To address this, our program implemented resident-led group feedback sessions. Methods: Residents provided group feedback to faculty through three Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles. PDSA cycle 1: Ten PGY-3 Medicine residents were trained to facilitate and transcribe group feedback for 20 ambulatory faculty. Ten cohorts of nine PGY1-3 residents met triannually to provide faculty feedback in a group setting without faculty present. PDSA cycle 2: The quality of faculty feedback from residents was evaluated using a modified narrative evaluation quality instrument (scale 0-10, higher is better). A subsequent round of resident-led feedback sessions occurred to collect longitudinal feedback on faculty, incorporating feedback from cycle 1. PDSA cycle 3: Replicated the procedures of previous cycles. Results: The primary outcome was feedback quality (using scales that quantified competencies addressed, specificity, and usefulness). The quality of feedback from residents to faculty significantly improved over three PDSA cycles. Total narrative quality scores increased from 4.9 to 8.1, with notable improvements in each subcomponent (higher is better): competencies addressed (0-4; 1.7 vs 3.3), specificity (0-3; 1.3 vs 2.2), and usefulness (0-3; 1.8 vs 2.7) (all p values < 0.001 pre- vs. post-intervention). The percentage of faculty evaluations completed by residents increased from 53% pre-intervention to 100% (N=127/240 vs. N=60/60). Discussion: Comprehensive facilitator training, dedicated time for feedback sessions, and feedback on the feedback process were implemented and perceived as key to overcoming these challenges. This approach ensured 100% of faculty received feedback throughout the year, covering multiple competencies with more specific and useful feedback. Conclusion: This innovation demonstrated that resident-led feedback sessions are feasible, valuable, and can be implemented without dedicated funding or additional resources.

Introduction

Effective feedback drives professional development and can improve teaching performance when timely, actionable, and credible [1]. However, collecting and providing constructive feedback to faculty is challenging, lacks uniform expectations, and is often non-specific [2].

Prior research has focused on providing feedback to trainees, with less attention to feedback for faculty. Literature suggests that structured feedback from residents to faculty can provide meaningful insights into teaching performance. While delayed, anonymized approaches may promote more constructive commentary, residents’ perceived barriers—including time constraints and reluctance to give critical feedback—may limit the effectiveness of upward feedback systems [3,4].

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) mandates annual faculty evaluations but offers limited guidelines on feedback expectations [5]. Learner assessments are a valuable source of feedback to faculty, with the potential to enhance teaching quality and professional development.

Trainee evaluations of faculty are used to assess faculty competency as teachers. While digital assessments can gather more feedback from learners, this does not always guarantee improved quality [6]. Additionally, the hierarchical nature of medical training can impede trainee feedback for faculty [7]. To maximize the impact of learner evaluations of faculty, it is essential to educate residents on how to construct comprehensive narrative feedback [2].

Objectives

We reviewed 240 resident-to-faculty evaluations from 2021–2022 as a needs assessment. Only 53% (n=127/240) were completed, with a high frequency of non-specific comments. Additionally, 30% (n=6/20) of faculty respondents to the ACGME Faculty Survey expressed dissatisfaction with the quality of feedback, citing a lack of timeliness, specificity, and perceived value, suggesting systemic barriers to meaningful feedback.

In response, we implemented triannual resident-led feedback sessions, allowing residents to create group narrative feedback for faculty, without faculty present, alleviating concerns about delivering feedback directly. We replaced the twice-yearly emails requesting individual feedback, which were delivered to preserve anonymity and mitigate concerns about reprisal, with triannual resident-led group feedback sessions. We measured feedback quality based on the competencies addressed (e.g., teaching, supervision, feedback), specificity and usefulness, and overall completion rates. While not intended as immediate performance feedback, these assessments aim to support faculty development through long-term reflection. The intervention targets residents by providing them with feedback on the quality of their feedback skills, fostering growth in this domain.

Two theories shaped the design of our intervention: Feedback Intervention Theory guided our emphasis on producing goal-oriented, specific feedback to support faculty improvement [8]. Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory influenced our use of active resident roles—such as curating and discussing feedback—to promote deeper learning through experience and reflection [8, 9]. Together, these theories framed the curation process as a meaningful learning experience for residents rather than simply a data collection task. These theories were applied to structure the resident feedback process, not to influence faculty response to feedback.

Methods

We conducted this project between 2021 and 2023 at two Internal Medicine clinics with 90 PGY1-3 residents, in 10 cohorts, each supervised by two faculty. Residents are split between these locations, each with five cohorts of approximately nine residents (N=90). Each cohort assessed two faculty members (N=20) during 30-minute feedback sessions occurring triannually. Residents spend 300+ hours annually with faculty, staffing encounters and attending didactic sessions. Cohorts and designated faculty remained consistent throughout residency, fostering continuity for evaluations. Of the 20 faculty, 12 are early-career physicians. Our quality improvement (QI) team included the PD, Clerkship Director, and a resident.

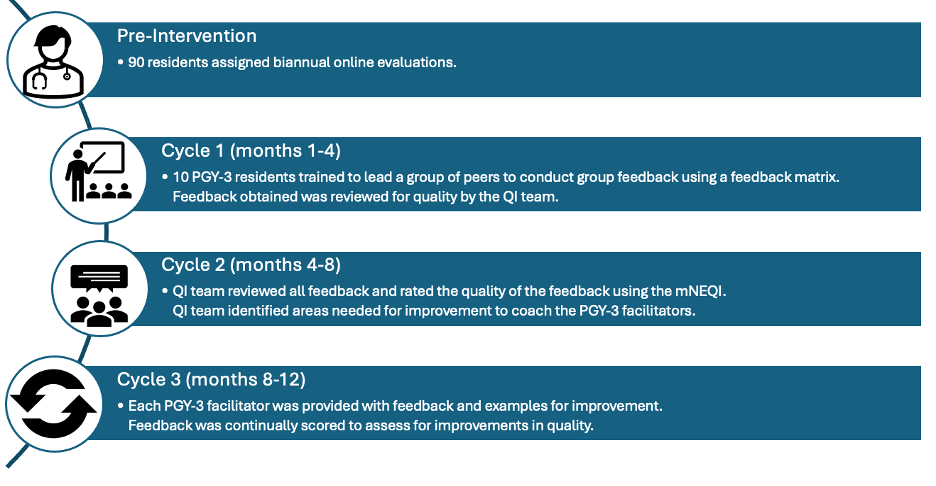

The intervention followed Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles, a process for testing and implementing changes: Plan an intervention, Do it, Study the results, and Act to refine and improve the process (Figure 1).

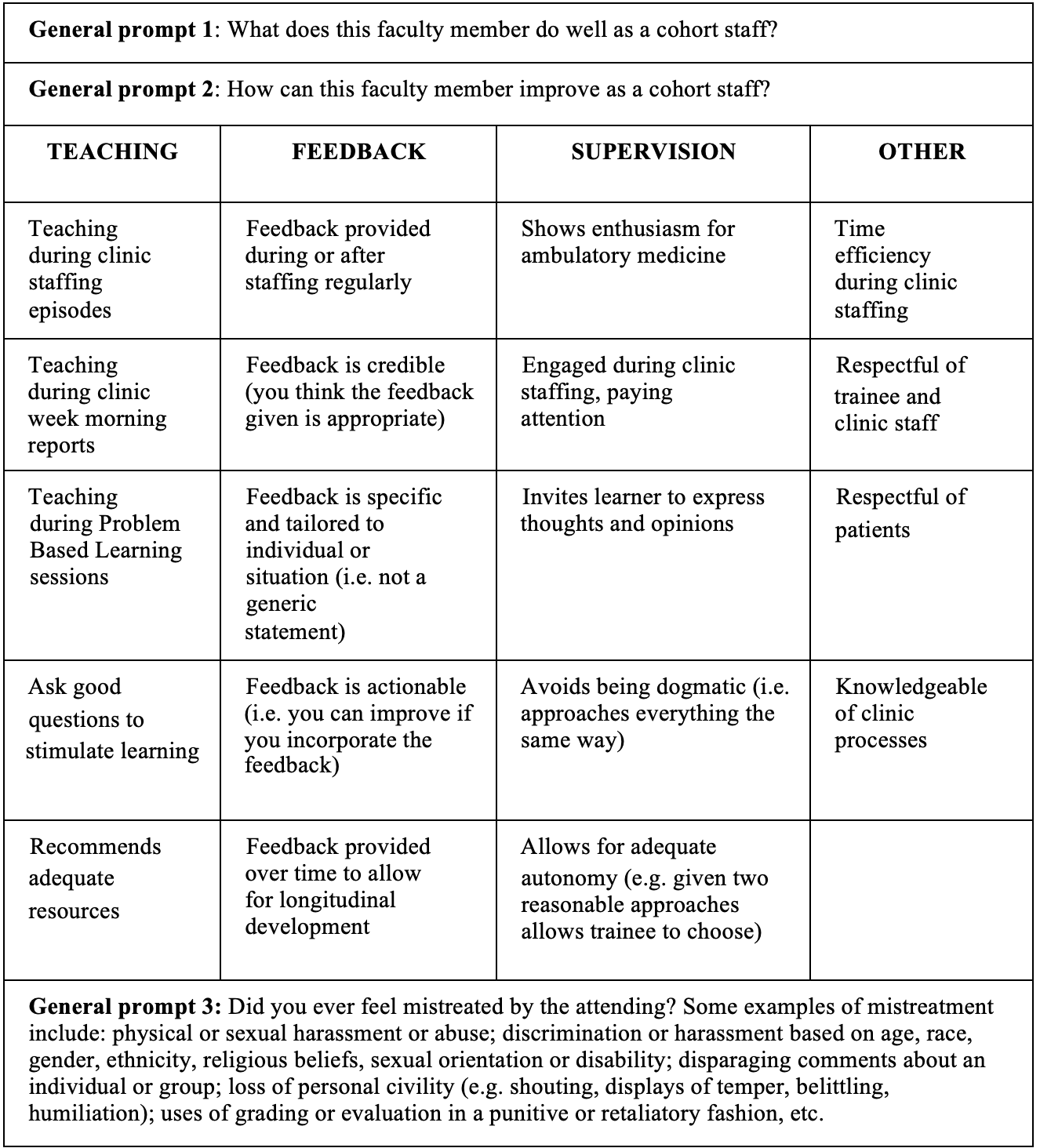

PDSA Cycle 1 (months 1-4): Ten PGY-3 leaders were trained to lead faculty feedback sessions using a structured matrix (Figure 2). Each leader received one hour of training. They led peer feedback sessions four months into the academic year using general prompts (e.g., strengths, areas for improvement) and focusing on key categories like teaching, feedback, and supervision. Suggested questions guided the discussion to ensure specific, actionable feedback within the time constraints. Curated feedback was entered into New Innovations (NI). The QI team reviewed feedback entries for completeness. To foster psychological safety, faculty were excluded from sessions.

PDSA Cycle 2 (months 4-8): To improve feedback quality, the QI team rated faculty feedback using the modified Narrative Evaluation Quality Instrument (mNEQI). Trends were reviewed in team meetings; raters resolved discrepancies by consensus. While inter-rater reliability was not calculated, this process aimed to ensure consistent feedback interpretation. The QI team identified areas for improvement to coach PGY-3 facilitators, emphasizing actionable and specific guidance to help refine their approach.

PDSA Cycle 3 (months 8-12): To reinforce improved performance, each PGY-3 facilitator was provided mNEQI ratings, feedback on deficiencies, and examples for improvement. Reminder emails were introduced for upcoming sessions and encourage the timely completion of evaluations. Feedback was continually scored to assess improvements in quality.

Background on the Design

Pre-intervention, 90 residents were assigned biannual online evaluations for each faculty member. Across three PDSA cycles, this was replaced by triannual group feedback sessions with nine residents led by their trained facilitator. These sessions added 90 minutes per year to their schedules. Facilitators conducted sessions every four months, entered feedback into NI, and the Program Director (PD) distributed it to faculty biannually. We recommend platforms that allow free-text entry, assign evaluations to facilitators, and share completed feedback with faculty, without endorsing any specific tool.

Facilitated sessions resembled focus groups, led by PGY-3 residents using a feedback matrix (Figure 2) as a guide. The matrix outlined key domains of effective teaching and included prompts to encourage discussion. Facilitators were not required to ask every question but were instructed to cover the major categories. Sessions varied slightly by facilitator style, but all aimed to generate specific, constructive, and balanced feedback in a faculty-free environment.

Facilitators took notes during each session and were responsible for summarizing the discussion into a narrative in NI. There was no formal analytic approach. Facilitators synthesized overarching themes but occasionally included direct comments. Final feedback was compiled afterward by facilitators, aiming to reflect group consensus while maintaining anonymity.

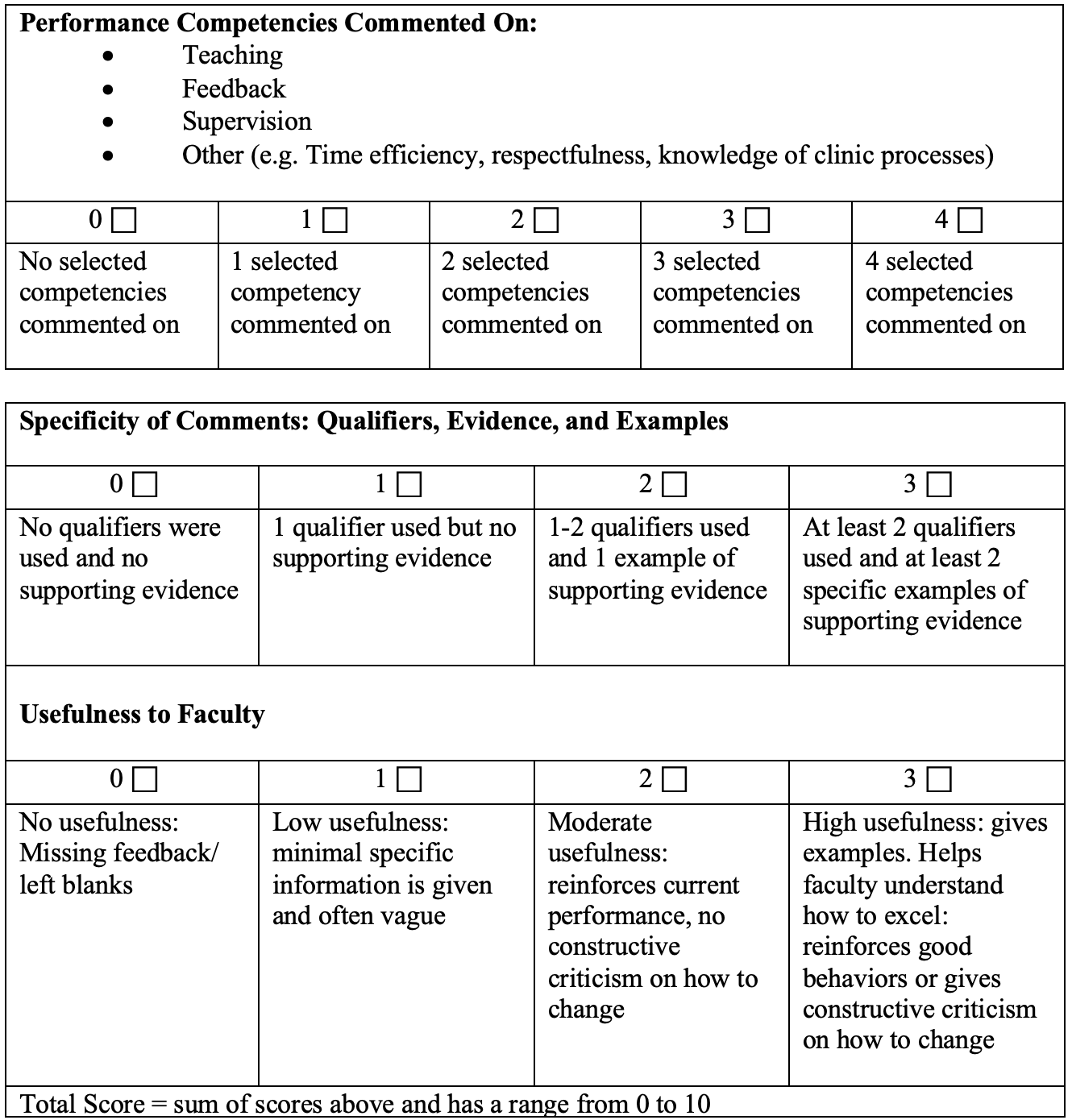

We used the mNEQI (Figure 3) to evaluate the quality of faculty feedback. Initially developed to assess the quality of neurology clerkship narratives, the NEQI scores three components (each on a scale of 0 to 4): performance domains addressed, specificity of comments, and usefulness to trainees [10]. These dimensions were identified as key indicators in a scoping review, highlighting their ability to reliably differentiate narrative evaluation quality [2]. This tool has demonstrated high internal consistency, reliability, and content validity in the context of evaluating faculty narratives of medical students [10].

We adapted the instrument (mNEQI) to assess residents’ feedback to faculty using a 10-point system: performance competencies commented on (maximum score 4), specificity of comments (maximum score 3), and usefulness to faculty (maximum score 3). We modified the number of anchors on two subscales for clarity and scoring consistency. The original NEQI lacked clear distinctions between scores of 1 and 2 for specificity, and we adjusted the usefulness scale from 0,2,4 to a 0-3 scale to include intermediate values.

Outcome Measures

1) Feedback quality was assessed using an mNEQI. An excellent rating required covering multiple competencies, providing specific, useful comments, and scoring ³8.

2) Completion rates by residents, comparing numbers of assigned vs. completed evaluations pre- and post-intervention.

The QI team compared pre-intervention to post-intervention to assess narrative quality and completion rates. The QI team conducted a comparative analysis of total and individual category mNEQI scores pre- and post-intervention. Means and standard deviations of scores were calculated, and differences among resident cohorts were analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis test. Significance for results was set at p-values <0.05, two-sided. Analyses were performed using JMPv13.2 (SAS Corp, Cary, NC). Completion rates were also analyzed pre- and post-intervention. Our Institutional Review Board determined the project exempt.

Results

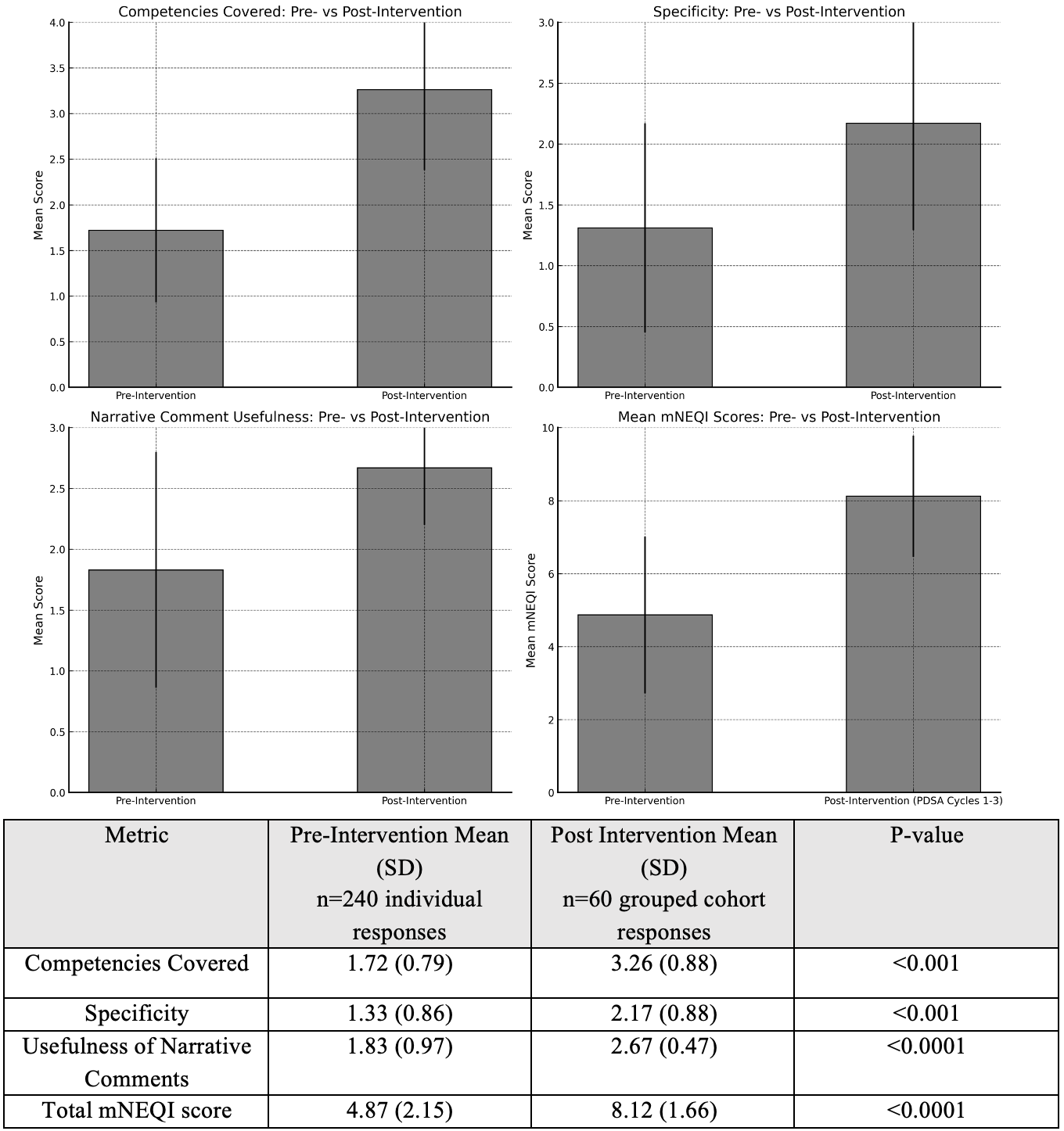

Pre-intervention, the mean score for competencies covered was 1.7 (SD 0.8) compared to 3.3 (SD 0.9) post-intervention (p < 0.001). Specificity scores improved from a mean of 1.3 (SD 0.9) to 2.2 (SD 0.9) (p < 0.001). Significant improvements were noted in specificity from PDSA cycles 1 to 3, with cycle 3 showing more specific feedback. Usefulness scores increased from a mean of 1.8 (SD 1.0) to 2.7 (SD 0.5) (p < 0.001) (Figure 4, Supplemental Figure 1). Pre-intervention, narratives ranged from 0 to 75 words, averaging 25. Post-intervention, narratives ranged from 60 to 275 words, averaging 150.

Pre-intervention, 127 of 240 evaluations (53%) were completed by residents, with a mean total mNEQI score of 4.87 (SD 2.15). In PDSA cycles 1-3, all evaluations were completed (100%), with a significantly increased mean total mNEQI score of 8.1 (SD 1.7) (p < .0001) (Figure 4). Pre- intervention, 30% (n=6/20) of faculty expressed dissatisfaction with feedback on the ACGME Faculty Survey, compared to 15% (n=3/20) post-intervention. Additionally, 90% of faculty felt they received feedback on an adequate number of competencies, 100% found the feedback useful, and 80% found it specific.

Discussion

Across specialties, faculty rarely receive structured, actionable feedback on their teaching. Although trainee feedback is a primary source, trainees are seldom trained to give it, and rarely receive feedback on the quality of their assessments. This model addresses both gaps. This intervention provides a curated narrative assessment to faculty, summaries of performance over time, that preserve resident anonymity and differ from immediate feedback conversations.

PGY-3 facilitators lead resident discussions to generate balanced, actionable input, while residents also receive feedback on their own evaluation skills. Although individual perspectives may be embedded within group feedback, the aggregated approach provided balanced, actionable insights and represented a meaningful improvement over the lack of consistent feedback pre-intervention. Though not designed for immediate performance changes, these assessments support faculty development, promote resident growth in communication, and ensure timely, meaningful feedback that advances learning and patient care. Its scalable design makes it widely applicable.

Resident-led feedback sessions are feasible, valuable, and were implemented without dedicated funding or additional resources. Training sessions lasted one hour, and feedback sessions took 30 minutes per PDSA cycle. Scoring resident feedback took two hours per cycle, and providing feedback to residents on their feedback took 60 minutes. Feedback sessions were incorporated into the existing multidisciplinary meeting without extending its duration. Residents expedited patient handoff, and the feedback discussions replaced the brief evidence-based practice presentations normally conducted during this time. While the educational focus shifted, overall instructional time was preserved. These findings emphasize the importance of effective planning and time allocation for successful implementation.

A key outcome was residents’ ability to effectively facilitate group sessions and collect peer feedback for faculty with minimal training. However, sustaining these skills requires ongoing deliberate practice and consistent guidance. Despite the overall improvement in mNEQI scores from pre- to post-intervention, only the specificity category showed statistically significant improvement between PDSA cycles. The decrease in mNEQI scores during the second PDSA cycle may reflect the “moderator effect” since scores max at 10, but more likely indicates the need for continuous reinforcement on how to construct comprehensive narrative feedback.

The feedback matrix developed for facilitator training was shaped by our experience and aligns with key ACGME Clinician Educator Milestones [11]. We selected competencies that we believed residents could reliably assess and provided relatable examples in our feedback matrix (Figure 2). Although the process requires annual retraining as new residents enter and advance through the program, this cycle serves as iterative learning rather than a sustainability challenge. Residents progressively refine feedback skills across their training, culminating in opportunities to facilitate as PGY3s. This structure reinforces feedback as a core, longitudinal competency consistent with the program’s educational mission.

Comprehensive facilitator training, dedicated time for feedback sessions, and feedback on the process were key to success. This approach ensured 100% of faculty received feedback throughout the year, covering multiple competencies with specific, useful feedback extending beyond positive reinforcement to include constructive suggestions. Higher completion rates were anticipated due to protected time, facilitator support, and feedback training. Residents in our program work long-term with two specific preceptors, which enhances the quality of feedback collected. While shorter faculty-resident interactions may reduce feedback depth, the model remains feasible. In our pilot, feedback was successfully collected for 20 faculty; scaling to larger programs (>100 faculty) may require more frequent sessions. The model ensures rich, actionable insights, particularly when residents have multiple encounters with each attending to identify patterns of teaching performance.

Resident acceptability for the intervention appeared high, evidenced by their compliance and high completion rates. However, this may not fully reflect true sentiment, as leadership involvement could have pressured compliance, discouraging open expression of concerns or dissent. All faculty regarded the intervention and the feedback process positively; however, not all the feedback they received was uniformly positive, as residents also provided constructive comments for improvement. Faculty were not informed in advance of the change in feedback format. The faculty’s lack of awareness of the change helped minimize potential bias in their responses.

A limitation is the lack of formal validation of the mNEQI tool, which may have impacted assessment specificity, although the modification was grounded in psychometric principles and should not harm internal consistency. While discrepancies in feedback grading were resolved through discussion, future efforts should focus on inter-rater reliability assessments. Future studies should explore the pressure residents may face as both feedback providers and receivers, and its impact on well-being. Qualitative data could offer insights into perceptions of faculty feedback, psychological safety, and the learning environment. Next steps include expanding to inpatient settings, gathering formal resident feedback on the process and faculty feedback on their perception of feedback, and exploring additional validity evidence for the NEQI tool modifications.

Conclusions

This intervention holds the potential to empower residents by developing skills in generating comprehensive narrative feedback for faculty. For faculty, it could prompt changes in teaching practices, foster self-assessment, and promote professional growth. This initiative equips residents with vital skills and enables the collection of robust faculty feedback, which can potentially inform performance meetings, faculty promotion decisions, and identify areas for improvement.

Tables and Figures

Figure 1. Timeline and description of PDSA cycles.

Figure 2. Matrix for PGY-3 Facilitators to Lead Peer Group Discussions and Construct Narrative Feedback for Ambulatory Faculty. This matrix provides a structured approach for third-year internal medicine residents (PGY-3) to facilitate peer group discussions and generate constructive narrative feedback for ambulatory faculty. It includes key discussion topics, feedback categories, and guidelines to ensure that feedback is meaningful and actionable.

Figure 3. Modified Narrative Evaluation Quality Instrument (mNEQI). Used by the Quality Improvement Team to Evaluate Feedback from Residents to Faculty. This figure illustrates the modified Narrative Evaluation Quality Instrument (mNEQI), which is used to assess the quality and effectiveness of feedback provided by residents to faculty. The mNEQI evaluates three key criteria: clarity, specificity, and utility of feedback. It employs a 10-point scale, with three components: performance competencies (maximum score 4), specificity of comments (maximum score 3), and usefulness to faculty (maximum score 3).

Figure 4. Comparison of Mean Modified Narrative Evaluation Quality Instrument (mNEQI) Scores for Evaluations Completed Before and After the Intervention. This figure compares the mean mNEQI scores for evaluations completed before and after the intervention. In the pre-intervention phase (2021-2022), residents completed 127 out of 240 evaluations (53%) on faculty. Post-intervention (PDSA cycles 1-3), all 60 assigned evaluations were completed (100%). The mean total mNEQI score significantly increased from 4.87 (SD 2.15) to 8.12 (SD 1.66) (p < .0001). Additionally, the figure highlights statistically significant improvements in scores for competencies assessed, specificity, and usefulness of narrative comments following the intervention, which included resident-led group discussions aimed at enhancing written feedback for faculty.

Details

Acknowledgements

None.

Disclosures

The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Defense Health Agency, Brooke Army Medical Center, the Department of Defense, nor any agencies under the U.S. Government.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Supplementary Files

References

- 1

Bing-You R, Hayes V, Varaklis K, Trowbridge R, Kemp H, McKelvy D. Feedback for learners in medical education: what is known? A scoping review. Acad Med. 2017 Sep;92(9):1346–54.

- 2

Chakroun M, Dion VR, Ouellet K, Graillon A, Désilets V, Xhignesse M, et al. Narrative Assessments in Higher Education: A Scoping Review to Identify Evidence-Based Quality Indicators. Acad Med. 2022 Nov 1;97(11):1699–706.

- 3

Finn KM, Healy MG, Petrusa ER, Borowsky LH, Begin AS. Providing delayed, in-person collected feedback from residents to teaching faculty: lessons learned. J Grad Med Educ. 2024;16:564–71.

- 4

Geringer JL, Surry LT, Battista A. Divergence and dissonance in residents’ reported and actual feedback to faculty in a military context. Mil Med. 2023;188:e2874–9.

- 5

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME common program requirements (residency): sections I–V [Internet]. Chicago (IL): ACGME; 2022 [cited 2023 Nov 14]. Available from: https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRResidency_2022v2.pdf

- 6

Plante S, LeSage A, Kay R. Examining online course evaluations and the quality of student feedback. J Educ Inform. 2022;3(1):21–31.

- 7

Ramani S, Könings KD, Mann KV, Pisarski EE, van der Vleuten CPM. About politeness, face, and feedback: exploring resident and faculty perceptions of how institutional feedback culture influences feedback practices. Acad Med. 2018 Sep;93(9):1348–58.

- 8

Kluger AN, DeNisi A. The effects of feedback interventions on performance: A historical review, a meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory. Psychol Bull. 1996;119(2):254–84.

- 9

Kolb DA. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. 1st ed. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice Hall; 1983.

- 10

Kelly MS, Mooney CJ, Rosati JF, Braun MK, Thompson Stone R. Education research: the narrative evaluation quality instrument: development of a tool to assess the assessor. Neurology. 2020 Jan 14;94(2):91–95.

- 11

Puri A, Raghavan S, Sottile E, Singh M, Snydman LK, Donovan AK, et al. New ACGME Clinician Educator Milestones as a Roadmap for Faculty Development: a Position Paper from the Society of General Internal Medicine Education Committee. J Gen Intern Med. 2023 Oct;38(13):3053–9.